By Nick Wilbur

In today’s fire truck market, there are a lot of departments putting new or new-to-them aerial devices in service.

There is also a greater number of newer members driving than before. So, I pose a simple but important question: What can your truck do? When you read “truck,” it means anything with a ladder, aerial, tower, or bucket on it. If you are placing a new truck in service, you should figure this out before it goes into service. If you have a truck in service currently, this should be a review. If this is not a review, this is your chance to get up to speed. In a perfect system, you would know all this information. But, we know that perfection is a luxury most of the time. Even if you do not own a truck, knowing what your neighboring trucks can do is important. This will help you give them the space they need to gain the access they need.

So, where do you start? It is important first to understand the operator’s manual. This manual will give you some of the parameters and help guide you on how your truck is supposed to operate and its limitations. This is also a determining factor of liability. If there was an incident with your truck and you were the driver, the first thing you would be asked is, “Did you follow the operator’s manual provided by the manufacturer?” This document is not foolproof, but it is the governing document of that vehicle. Operating outside its guidance, you will own the liability. If you do not have access to this document, you can reach out to your truck’s manufacturer to obtain one. The new National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1900, Standard for Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting Vehicles, Automotive Fire Apparatus, Wildland Fire Apparatus, and Automotive Ambulances, requires aerial apparatus to always have an operator’s manual on the truck. This speaks to the importance of this document. Once you read and understand this document, you will have to pick a suitable place to put the truck through its paces. This spot may be one of many spots because we might want to look at how this vehicle handles different terrain and obstacles. Usually, the front ramp of the firehouse is not the right spot. Many firehouses have overhead wires across the front ramp, or the front ramp is on a slope. You want to ensure you are in a controlled environment when exploring your truck’s options.

1 Setting up a ladder truck in an open area to put it through its paces. Pick a level area where there are no overhead obstructions. (Photos by author.)

2 A rear-mount tower uses the “squat” by raising the front outriggers and lowering the rear to get the bucket to the ground in a shorter distance.

3 Setting up the truck in multiple spots allows the operator to navigate different terrain and see how the truck will react. Notice how high the ladder bed is before the truck’s outriggers are even set.

Let’s first cover a few key terms that are important to understand:

Scrub area: The area that the end of your aerial device can reach on a building or in space.

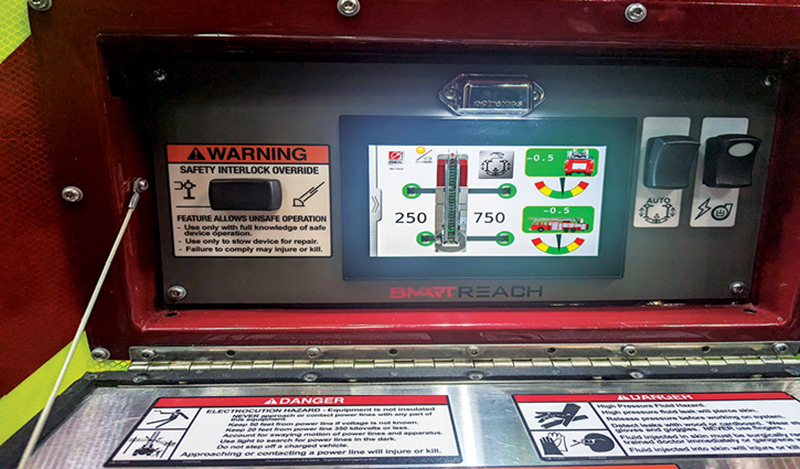

Interlocks: These limit the aerial’s functions. They are in place to prevent the truck or operator from entering into an unsafe or unstable condition. These are not foolproof, and trucks still require trained operators.

Override: This is a switch or control that allows you, as the operator, to use the aerial where the truck tells you not to. You would need to use this feature for short jacking operations in older trucks. Most trucks now remove all safeties and give full operation once this is engaged until the aerial is bedded again.

INTERLOCKS

First investigate or review your truck’s interlocks. Interlocks limit the movement of the aerial to prevent the aerial device from going into an unwanted position. You can explore your interlocks by putting the outriggers in many different configurations to see what the limitations are on your aerial device.

The easiest and most known interlock is the short jack interlock. Not all trucks have this interlock, so you want to check by short jacking one side of the outriggers. This is done by not fully extending your outriggers horizontally but still extending the outriggers down vertically until you make ground contact. The safest way to test the short jack operation is to stop the outrigger just before the full horizontal extension. Usually, the aerial will stop at 5 degrees past the center line toward the short-jacked side. For older trucks, this would be something you would have to use the override controls or switch for.

4 A newer jacking system that allows for jacks to be deployed short and adjusts the allowable tip loading instead of limiting aerial operation.

One thing that gets overlooked in some trucks is placing the outriggers straight down to the ground on both sides to see if you can get the aerial device out of the cradle. This can be called no-jacked, but it is essentially short jacking on both sides of the truck. This largely depends on the manufacturer, type, and year the truck was built. This information is useful for rear-mount aerial devices since you can pull in and use the aerial off the front. For midmounts, you would have to back in to see the same results. Some will allow operation straight off the truck with no reach limitation. This is going to depend on your truck, which is why it is important to explore all possibilities during training first.

When learning about your aerial, it also helps to understand how its weight loading works. When you operate the aerial device above the 45-degree mark, most of the weight comes straight down the chassis and is distributed pretty evenly into the outriggers. This helps paint a picture of what loading the outriggers will receive.

The same could be said about working off the front of a rear-mount truck. The chances that the vehicle will tip over frontward with all wheels on the ground are very slim. With that in mind, if someone was trapped in an upper window, just line the windshield up with the victim and you don’t have to worry about the horizontal space for the outriggers. You would place them straight down and be able to operate directly off the front of the truck. Again, this is for a rear-mount aerial and should be understood and practiced.

Anyone with a midmount is going to have to play that same thought process out, just by backing in instead of pulling in.

Remember that tip load is not a constant. Variables like water flowing, gallons of water flowing per minute, angle of water flowing, wind condition, ice accumulation, extension of aerial, and angle of aerial can all affect tip loading. It is important to understand the loading of the truck’s aerial device as well as the load chart provided by the manufacturer.

Another interlock that may be present is the front axle interlock. First, investigate if you have one. The best way to do that is to try it out. Take the front axle off the ground when jacking the truck up. Ensure there is nothing in the operator’s manual that prevents you from lifting axles off the ground first. You are then going to operate the aerial to see if there are any limitations on where it can go. Some devices will limit the reach of the aerial at the front of the truck. As before, you will operate the aerial device and see where it stops you. One thing to consider is the angle of the aerial and the amount of extension allowed. When the ladder truck has its front wheels off the ground, some trucks will have only 77 feet of extension out of 100 feet at 5 degrees. But at 75 degrees, it has full extension. This is because the tip of the aerial isn’t any farther away from the base of the truck. Imagine a wall in the front of the truck is what will stop you when your front axle is off the ground. Trucks are different, so try yours out. An important thing to note is that if you have an older vehicle with straight hydraulic controls, you will most likely not have this type of interlock.

What happens if the jacks lose ground contact? This was the early sign of tipping over and ladder failure for many years. Today, many aerials allow for the outriggers to lose contact if the truck is not jacked up off the suspension. This means that when deploying the outriggers, you need to obtain the green light or engage the pressure sensor and then keep engaging the outrigger until the tire is just off the ground.

With the suspensions in the newer vehicles, there is a decent amount of travel that needs to be accounted for to ensure your outriggers do not lose contact. Again, losing ground contact has been said to be acceptable by the aerial engineers, but if you or your department is uncomfortable with it, just keep jacking. One note of caution: When raising the outriggers, you want to pay attention to what equipment you will need access to. You can quickly make something inaccessible by raising the outriggers too high.

5 A real-time shot of different types of trucks with different aerials and different jacking systems operating together. Knowing your truck and your neighbor’s truck helps with positioning on the fireground.

COLLISION AVOIDANCE

We can look at the aerial now to see if it has collision avoidance. The older your vehicle, the less likely it is to have this technology. A word of caution: Collision avoidance works with everything in a stowed position. If you place a ladder on the side of your truck or open a compartment, the truck does not know this and will hit it if you, the operator, don’t stop it. Nothing replaces a trained operator at the controls. What we are looking for here is where the truck will stop you.

We have seen trucks that stop you at 24 inches short of a potential collision point. This is unacceptable for the manufacturer to allow and for the fire department to accept. There is currently no standard on how far collision avoidance is programmed for. The customer is on the hook to try it out during the final inspection and ensure it is “dialed in” to the specifications or desires of the fire department. Remember, an inch here turns into feet at 100-foot extension. One truck lost two full floors of access due to a computer programming issue that would require override operations by the operator to overcome.

I may say it too much, but if you do not know, you need to ask for help. This doesn’t have to be an expert necessarily. It just needs to be someone who has been there and knows the subject. At this point, with the Internet and connectivity, you can reach out to anyone in the country for advice and should be doing just that. A neighboring fire department does not have to be right next door.

Lastly, you want to capture some useful information about your truck. How far do you have to extend the aerial at the lowest angle to touch the ground? Can you manipulate how the truck is set up to improve this? For instance, you can overextend the nonoperational side outriggers vertically and lower the operational side outriggers. Just operate the truck at the maximum allowable degrees, still with full operation. Some call this the “squat.” This operation allowed the tower I operate off of to hit the ground at 40 feet off the rear instead of 65 feet. What is the maximum horizontal reach of the aerial? How far can your outriggers extend into the ground?

You also want to understand how far your truck has to be away from a structure to meet the maximum height. This is an important figure in midrise and high-rise buildings. Finding and writing the numbers down is not for you to memorize them. It is for use and consumption. If you don’t know the numbers and understand the numbers, you won’t know what the aerial can do and its limitations. Using known measurements in your response area, these numbers can fade to practical knowledge.

For instance, a standard road is 12 feet wide to the center line, a street-side parking spot is 8 feet wide, and the standard sidewalk is 4 feet wide. If you position your turntable on the center line, you will be around 24 feet away from the building. This piece of information is much easier to communicate to other units, rather than saying, “I need 24.6 feet of space.”

This is the tip of a very long spear of information. As the operator, it is up to you to be thirsty for information. Stay informed on the changes to apparatus and how they operate, especially if you receive one or are specifying one. Seek training regionally and nationally at any of the trade shows to increase your knowledge base. Always question the manufacturer to ensure you fully understand the apparatus you are paying for. And lastly, get out with your apparatus and “stretch its legs.” The last thing you want is to show up with a $2 million piece of equipment and not be able to complete the job it is built for and capable of doing.

NICK WILBUR is a firefighter/EMT for the Arlington County (VA) Fire Department and a captain in the College Park (MD) Fire Department. He writes for Fire Engineering and was a HOT instructor at FDIC International for ladder placement. He works for EVR, conducting training and specification services.