By Bill Adkins and Andy Soccodato

Water supply operations in the rural setting comprise some of the most challenging scenarios that firefighters face. These challenges are magnified when companies are not equipped with the necessary tools to efficiently operate in the rural environment.

This article serves to highlight some of the most important pieces of equipment that should be on every rural engine company to seamlessly perform water supply functions at a rural fire incident.

Some of the equipment mentioned in this article is likely equipment your engine company is already carrying. Other pieces may be items that your department considers budgeting for and purchasing in the future. Regardless, each item listed allows the rural pump operator to reliably perform his duties on the rural fireground regardless of whether the item costs several thousand dollars or only a few dollars. Some of these items can be added to the apparatus as soon as you finish reading this article; however, other items may need to be considered as part of the next apparatus purchase. The items discussed should be considered essential pieces carried by companies that routinely operate as part of a rural water supply operation.

INTAKE VALVES

Intake valves are arguably some of the most important pieces of equipment that should be on the rural engine company. For the context of this article, we are referring to intake valves specifically for the large 6-inch steamers, or master intakes on the pumper. Intake valves take the form of either internal or external valves. Internal intake valves are typically spec’d during the purchase of a new pumping apparatus, whereas external intake valves can be incorporated on the pumper at any point in its service life. Regardless of the intake valve style, firefighters should remember that this tool allows the pump operator to control the flow of water into and out of the pump.

One of the major advantages of internal intake valves is that they typically have larger waterway openings compared with their external counterparts. Another advantage is that because they are integral to the internal pump plumbing, this configuration typically results in less protrusion outward from the driver’s and officer’s side pump panels. The obvious major disadvantage of this configuration is that repairing these valves tends to be more labor-intensive since panel components must be removed for a mechanic to access the valves. While it is possible to retrofit an existing apparatus with an internal intake valve, it is likely not fiscally responsible to do so. Therefore, it is best to consider this as an option during the build process for a new apparatus.

The major advantage of an external intake valve is that it can be added to the apparatus at any point during the service life of the rig. However, firefighters must understand that not all external intake valves are created equal. While fire departments can purchase external intake valves from several manufacturers at various prices, be wary of which valve you choose to buy. The internal waterway of a particular external intake valve can vary significantly depending on the valve manufacturer. Internal waterway diameters vary from 5¼ inches on the large end of the spectrum all the way down to 3½ inches on the small end (photo 1). Placing an external intake valve with only a 3½-inch waterway on the 6-inch steamer of a pumper will drastically diminish the flow rate through that particular intake. This will be even further exacerbated when the pumper is operating from a draft, as many external intake valves with 3½-inch waterways struggle to achieve 1,000 gallons per minute (gpm) during these operations.

Departments looking to outfit their rural engine companies with external intake valves should always lean toward purchasing the intake valve with the largest waterway possible. This is especially important for organizations that routinely draft. This will allow higher flow rates to be achieved during a drafting operation. In addition, fire departments that routinely operate from a draft should consider outfitting their external intake valve with 6-inch male threads on the inlet side of the valve. This will make connecting hard sleeve to the intake valve extremely easy while also ensuring that the connection can be made airtight with a mallet (photo 2). To allow the intake to be usable for pressurized water operations, fire departments can keep a 6-inch female-to-Storz adapter on the intake valve as a standard practice (photo 3). In the event the pumper is forced to draft, the operator can simply pop off the adapter and then connect the hard sleeve directly to the intake valve.

While it is certainly possible to operate a fire pump without an intake valve, doing so severely limits the capabilities of the pump operator and the water supply operation. Many rural engine companies simply keep a blind cap on their 6-inch steamer or master intakes. When a drafting operation is required, the pump operator removes the cap, connects the hard sleeve, and activates the primer to achieve a prime for the static source. This is absolutely acceptable as long as the positive displacement primer pump works. If the primer fails to operate, this can be a challenging scenario to recover from. Intake valves provide the pump operator the option of performing alternative drafting techniques that do not require the use of a primer. If the primer fails to operate, the operator can easily perform a burp draft to achieve the prime. For more information on burp drafting, refer to the Fire Apparatus & Emergency Equipment article “Burp Drafting: An Alternative Primer-Less Priming Method” (September 2022).

The other major advantage of equipping each pump intake with an intake valve is that it allows the pump operator to draft through multiple intakes simultaneously (photo 4). Multiple intake drafting is the fastest and most efficient means to increase the flow capability of a drafting operation. Intake valves allow the pump operator to perform these operations seamlessly because the operator can control the priming of each intake being used. Typically, these operations are performed in segments as equipment becomes available. This means the operator will prime the initial intake while equipment is gathered and assembled for the second intake used. Having an intake valve on both intakes being used allows the pump operator to control the priming process.

If the strainer on the second intake being primed is equipped with a jet siphon, the operator can perform the pressurized priming process to expel the air in the hard sleeve before the second intake valve is even opened. In situations where the second intake valve is equipped with only a barrel strainer, having intake valves on both the intakes being used allows the operator to briefly shut down the flow and close the initial intake. Closing the first intake will maintain the prime in that line while the operator primes the second intake being used. Once the second intake is primed, the operator can reopen the initial intake valve and begin flowing water again.

HARD SLEEVE

Hard suction hose, or “hard sleeve” as it is commonly called, is one of the hottest commodities on any rural fire scene. For rural fire companies, this is likely equipment that is already being carried on your apparatus; however, the question becomes, “Are you carrying enough hard suction hose?” Previously, NFPA 1901, Standard for Automotive Fire Apparatus, required that pumpers carried either 20 feet of hard sleeve or 15 feet of soft suction hose. With NFPA 1900, Standard for Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting Vehicles, Automotive Fire Apparatus, Wildland Fire Apparatus, and Automotive Ambulances, however, it is up to the authority having jurisdiction to determine how much hard sleeve should be carried on its fire department pumpers.

Many fire departments still believe that 20 feet is a sufficient amount of hard sleeve to carry on their pumping apparatus. The reality is that two 10-foot sections of hard sleeve is typically insufficient for more complex rural water supply operations (photo 5). More advanced water supply operations are often delayed as firefighters wait for additional apparatus to arrive with extra lengths of hard sleeve. Common rural water supply operations that require in excess of 20 feet of hard suction hose include water transfer between multiple dump tanks, drafting through multiple pump intakes, and reaching distant water sources.

Rural fire companies that routinely operate from static water sources should consider carrying more than 20 feet of hard sleeve on their apparatus. Not only does this allow individual companies to become more self-sufficient on the rural fireground, but it also increases the total amount of hard sleeve available to both the dump and fill sites. Generally speaking, for organizations that routinely draft, a good number to strive for is 50 feet total of 6-inch hard suction hose carried on each pumper. At a fill site, this allows the pumper to reach a more distant source or perform a twin-tube draft with its own equipment. For dump site operations, close to 50 feet of hard sleeve is usually needed to establish a prime from the primary dump tank and set up water transfer lines for multitank operations. Fire departments should also consider carrying larger quantities of hard sleeve on their mobile water shuttle apparatus as well. This is because these apparatus can potentially bring extra lengths of hard suction hose to units operating at both the fill and dump sites.

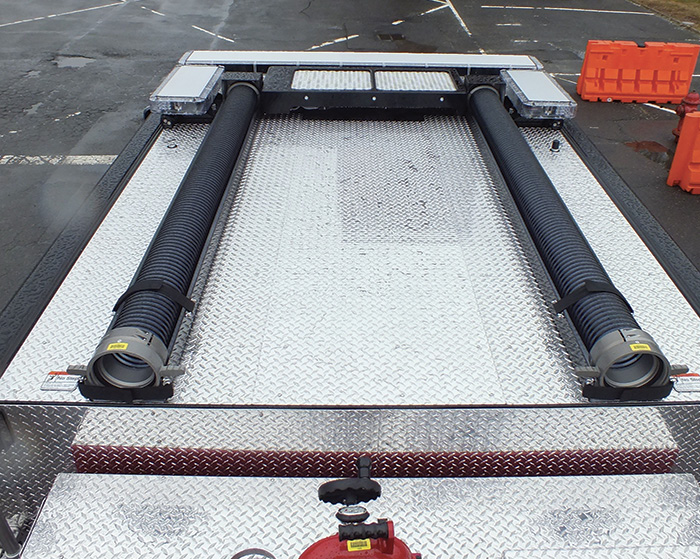

The next question that is often asked is, “Where are we going to carry this additional hard sleeve on the pumper?” A traditional storage option is for hard sleeve to be carried on the upper driver’s and passenger’s side portions of the pumper’s body. This is an easy way to carry at least 20 feet of hard sleeve. Double stack hard sleeve racks are also available that allow for 20 feet of hard sleeve to be carried on each side of the pumper body (photo 6). Departments should be mindful of the potential effect this may have on the overall height of the apparatus. Another option for apparatus equipped with flat cab roofs is to carry hard sleeve in racks on top of the roof. This is a simple way to carry additional suction hose in a location that would otherwise be considered wasted space (photo 7). Firefighters should note that because of cab dimensions, air conditioner layouts, and lightbar configurations, the hard sleeve lengths carried on the cab roof may be shorter than 10 feet.

One example of a purpose-built rural water supply pumper is the Glen Gardner (NJ) Volunteer Fire Company’s Engine 12. This rig serves as the first-out pumper in a rural portion of Hunterdon County, New Jersey, and was built to carry a multitude of hard sleeve without sacrificing the attack and supply hose quantities in the rear hosebed. Engine 12 carries a total of 88 feet of 6-inch hard sleeve, 20 feet of 4-inch hard sleeve, and 20 feet of 3-inch hard sleeve within the rear body of the apparatus (photo 8) This is in addition to the 1,800 feet of 5-inch supply line, 500 feet of 3-inch supply line, 500 feet of 2½-inch attack line, and 500 feet of 1¾-inch attack line stored in the rear hosebed and the 1,000-gallon onboard booster tank. While not every rural engine company needs to be built this way, it is critically important to recognize the advantage to purpose-built apparatus when it comes to rural water supply operations. Engine 12’s layout and configuration allow the Glen Gardner Volunteer Fire Company to efficiently perform attack engine duties by deploying front bumper lines and preconnected crosslays while simultaneously allowing for effective water supply operations from the rear of the apparatus.

STRAINERS

In rural settings, where hydrants are not an option, fire apparatus operators must expect to use some type of strainer when drafting. There are various types of strainers in the water supply world, and it is important to use the proper strainer for the right scenario. One must also know that not all strainers are created equal. Different strainers have a vast range of flow capabilities depending on their designs. Please do some homework by knowing their maximum flows and order the strainer that coincides with your particular operation.

Lakes and ponds are great sources of water supply in rural areas. The apparatus will have the ability to pump at its rated capacity and beyond. When receiving water from lakes and ponds, you will want to prevent sediment from entering the pumps. A way to prevent this from happening is using a floating strainer (photo 9). Floating strainers are easy to deploy and do not require the operator to estimate if the strainer is too close to the bottom. There are floating strainers on the market that have jet siphon capabilities and, if they don’t, you can purchase an adapter to the strainer to create a jet siphon if needed.

For dump tanks and pools, a low-level strainer will assist the operator in getting as much of the available water as possible (photo 10). Using a barrel strainer will start sucking air in about 10 to 12 inches of water, whereas a low-level strainer will allow operators to maximize water consumption and will not cavitate until 3 to 4 inches of water are left in the tank. Buyers, be aware—low-level strainers have a wide range of flow capabilities. Sometimes you get what you pay for. If you’re not planning on flowing large amounts of water, the less expensive strainer may be all you need. However, if you have multiple large fire loads in your area, you may want to spring for the high-flow low-level strainer. We highly recommend getting a low-level strainer with a jet siphon connection. A jet siphon produces a couple of options, like assisting with your draft and if you need to move water from one dump tank to another.

A few manufacturers make combination strainers (photo 11), floating strainers that can be low-level strainers as well. If compartment space is tight, one of these strainers may be what you need. Instead of needing space for two or three different strainers, the combination strainer consolidates them into one. Another space-saving tip is to connect your strainer to the hard sleeve hose while stored on the apparatus (photo 12). This also prevents the operator from needing to connect the strainer when on scene and at times when seconds count.

SEALANTS

Drafting consists of creating a negative pressure in the pump to allow atmospheric pressure to force water from a static water source into the pump. To create this negative pressure, the operator must be sure that there are no air leaks in the system. Making sure drains are closed and all intake fittings are tight is essential in creating this negative pressure.

The use of an intake valve (either internal or external) is helpful when drafting. This prevents the loss of pressure when discharging to a crew or to another apparatus and aids in controlling water loss from the intake. When you use an external intake valve that has not been properly maintained, air leaks may appear. This does not mean that your intake valve needs to be removed.

Most of the time the air leaks on external intake valves come from the connection to the valve from the hard sleeve. Other leaks may stem from the bleeder valve. A simple fix to these leaks is duct tape at the area of concern. If duct tape doesn’t work, then the leak may be coming from an area not yet sealed. Wrapping cellophane around the entire valve (excluding the valve handle) proves to mitigate those air leaks.

When using Storz fittings, using a drafting gasket, duct tape, or cellophane wrap is a must. Drafting gaskets are slightly thicker than normal Storz gaskets and have a small lip on them to create a seal between connections. Keep in mind, using Storz fittings will reduce the amount of maximum flow. If large volumes of water are needed, it is recommended that operators use a threaded fitting.

BILL ADKINS is a captain with the Loveland-Symmes (OH) Fire Department Training Division/Maintenance Division. He is on the Editorial Advisory Board for Fire Apparatus & Emergency Equipment.

ANDY SOCCODATO has served in the fire service for the past 17 years. He spent nine years of his career as a firefighter and driver/operator for the Charlottesville (VA) Fire Department. He is a full-time fire instructor II at the Tennessee State Fire Academy, where he oversees the driver/pump and aerial programs. Soccodato is the owner of The Water Thieves, LLC, which specializes in delivering street smart driver/pump operator courses. He is on the Editorial Advisory Board for Fire Apparatus & Emergency Equipment.

Bill Adkins will present “Rural Water Movement Operations” at FDIC International in Indianapolis, Indiana, on Wednesday, April 17, 2024, 10:30 p.m.-12:15 p.m.

Andy Soccodato will present “Advanced Drafting Operations: Getting Greedy with Your Water in the Rural Environment” at FDIC International in Indianapolis, Indiana, on Friday, April 19, 2024, 10:30 p.m.-12:15 p.m.