Drive to Survive: Case Studies Chris Daly

On April 7, 2002, a 29-year-old firefighter was responding to a reported brush fire in a fire apparatus with two other firefighters. As the fire apparatus rounded a curve, it began to leave the roadway and travel on the right road shoulder.

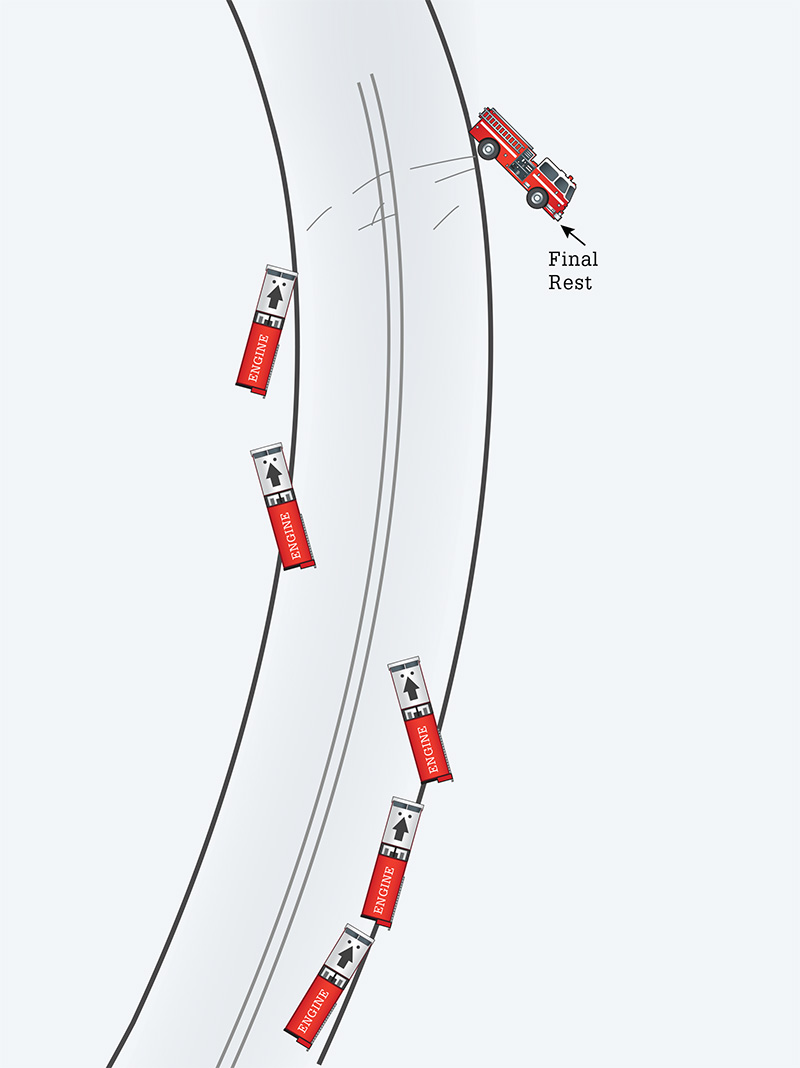

The driver overcorrected, causing the vehicle to reenter the roadway, cross both lanes of traffic, and leave the left side of the road. The driver once again overcorrected, causing the vehicle to roll over and come to rest on the right side of the road (Figure 1). During the crash sequence, the 29-year-old victim firefighter was trapped in the vehicle and sustained fatal injuries.

- Siren Limitations and Intersection Safety

- Ruptured Apparatus Tire in Oregon

- Lessons Learned from Fatal CA Apparatus Crash

- Video: Apparatus Rollovers

DRIVER CONSIDERATIONS

An investigation revealed that the engine involved in this crash was traveling approximately 74 miles per hour (mph) in a posted 45-mph zone. At no time should a fire apparatus be driven so fast, especially on a rural road and while rounding a curve. It should come as no surprise that the fire apparatus operator lost control.

There are many issues related to operating a fire apparatus or emergency vehicle at an excess speed. As speed increases, the kinetic energy associated with the moving fire apparatus will also increase. As a result, it will take a fire apparatus operator a longer time and distance to burn off the kinetic energy and bring the apparatus to a safe stop. For this reason, as speed increases, so does the stopping distance of the vehicle.

As speed increases, the fire apparatus operator’s perception and reaction distance will also increase. The faster a vehicle is traveling, the longer the distance it will travel as the fire apparatus operator recognizes a problem ahead and decides what evasive action to take. When this additional perception and reaction distance is combined with the additional braking distance, it is obvious that as speed increases, so does the time and distance it will take to bring the apparatus to a stop.

In addition to stopping the vehicle, there are other safety issues associated with excess speed. As speed increases, so does the amount of G-force acting on the vehicle. Excess G-force can lead to a rollover crash or loss of control, especially while rounding a curve. Excess speed can also lead to a brake fade situation as the brakes will have to work overtime to burn off the vehicle’s extra kinetic energy.

DRIVER TRAINING CONSIDERATIONS

Driver training programs should address the significant issues related to excess speed. Using a low center-of-gravity vehicle and a trained emergency vehicle operator (EVOC) instructor on a closed course, students can be shown how stopping distance and G-force will increase as speed increases. Classroom training should also address how perception and reaction distance increase with an increase in speed.

When discussing speed-related safety issues, driver trainers should also include an overview of brake fade and how to avoid succumbing to a brake fade situation. Should a fire apparatus operator drive the vehicle at an excess speed and suffer a brake fade situation, the driver could lose the ability to bring the vehicle to a safe stop if there is a cascade failure of the braking system.

In addition to addressing safety issues, driver training programs should discuss the significant liability issues related to unsafe speed. Should a driver operate an emergency vehicle at a high rate of speed and become involved in a crash, there may be criminal sanctions in addition to civil sanctions. In other words, you may get arrested in addition to getting sued. No one wants to go to jail for driving a fire apparatus in a reckless fashion.

It is important to note that this was the first time the fire apparatus operator had driven this vehicle to an emergency call. Fire department driver training programs should include a graduated process for qualifying a fire apparatus operator to drive a particular vehicle. After classroom and hands-on training, the newly minted fire apparatus operator should be required to drive to a number of emergency calls while under the mentorship of a trained driver training instructor or with an officer who is riding in the apparatus with them.

Figure 1: Diagram of the crash sequence. (Courtesy of NIOSH.)

RELEVANT NATIONAL FIRE PROTECTION ASSOCIATION STANDARDS

- National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 1451, 4.3.3: The [fire and emergency service organization (FESO)] shall establish written standard operating procedures for safely driving, riding within, and operating FESO vehicles during an emergency response.

- NFPA 1451, 4.3.6: Procedures for emergency response shall emphasize the safe arrival of FESO vehicles and occupants at the destination as the first priority.

- NFPA 1451, 4.3.10: Members shall be trained to operate specific vehicles or classes of vehicles before being authorized to drive or operate such vehicles.

- NFPA 1451, 4.3.10.1: Members shall not be expected or permitted to drive or operate any vehicles for which they have not received training.

- NFPA 1451, 4.3.10.2: Members shall be reauthorized annually for all vehicles they are expected to operate.

- NFPA 1451, 6.1.1: FESO vehicle drivers/operators shall have knowledge of applicable federal, state, provincial, and local regulations governing the operation of FESO vehicles.

- NFPA 1451, 7.1.1: The authority having jurisdiction shall have written policies governing speed and the limitations to be observed during inclement weather and under various road and traffic conditions.

- NFPA 1451, 8.2.2: The driver/operator of an FESO vehicle shall be directly responsible for the safe and prudent operation of the vehicle under all conditions.

- NFPA 1451, 8.2.3: Where the driver/operator is under the direct supervision of an officer, that officer is responsible for the operation of the vehicle.

- NFPA 1451, A8.2.2: The driver of any vehicle has a legal responsibility for its safe and prudent operation at all times.

- NFPA 1451, A8.2.3: While the driver is responsible for the operation of the vehicle, the officer is responsible for the actions of the driver.

RESOURCES

1. “Drive to Survive,” Fire Engineering, February, 2006, https://bit.ly/4b5WP2C.

2. “Introduction to Braking Energy,” Fire Apparatus & Emergency Equipment, August, 2015, https://bit.ly/3U7YPkV.

3. “Drive to Survive: The Art of Wheeling the Rig,” Chapter 1 –EVOC textbook available from Fire Engineering Books, which explains fire apparatus stopping distance in greater detail.

CHRIS DALY is a 25-year police veteran and an accredited crash reconstructionist. In addition to his police duties, he has served in the fire service for more than 33 years, including time as both a career and volunteer firefighter, holding numerous positions, including assistant chief. Daly has a master’s degree in environmental health engineering from Johns Hopkins University and is a contributor to Fire Apparatus & Emergency Equipment and Fire Engineering. He developed the “Drive to Survive” emergency vehicle driver training program, which he has presented to more than 26,000 firefighters and police officers across the United States and is the author of Drive to Survive—The Art of Wheeling the Rig (Fire Engineering Books).